In 1689 the merchant John Farmer complained to the Earl of Nottingham that he and a companion had been imprisoned at Beaumoris without accusation or warrant. Although held only two days before being brought to the Mayor and let go, he was “damnified in business and health.”[1] Donald Trump would no doubt have called it a case of “catch and release.”

Being detained, whether for hours or months, can be described as a minor inconvenience or life-damaging trauma. Much hinges right now on how we as a society choose to understand the purpose of detention and its relationship to punishment. Yet, we have a surprisingly long history of confusion on just these questions.

The particular evil of detention is its ambiguity. On the one hand, there is a long tradition in Anglo-American legal culture of sharply distinguishing detention and punishment. The medieval English jurist Henry Bracton was often quoted as saying that that a prison ought to be kept for confinement and not for punishment. Yet, in practice there have always been elements of pain and punishment in detention that muddy the distinction: the reason that people are entitled to a speedy trial, for example, is that detention is really too much like punishment.

Because detention is technically not the same thing as punishment, though, it flies under the radar of both law and scholarship. Oceans of ink have been spilled on the history of punishment, the rise of the penitentiary, and the catastrophic effects of late-20th century sentencing policies. But no one has written a history of detention as such. The legal parameters of detention are also hazier than those of punishment. We make laws about what kinds of punishments are appropriate for what kind of crimes, but detaining is seen as an administrative matter rather than a question of justice. Decisions that have huge human consequences – say, the use of cages and Walmarts, or flying kids to NY State while their parents are jailed in Texas, or refusing entry into appropriate asylee-reception centers — –can all be justified as matters of space, efficiency, convenience. It is telling that a Bush administration pilot program in “getting tough” by prosecuting immigrants in criminal court was dubbed “Operation Streamline,” the name deceptively suggesting that the prime consideration was efficiency. [2]

The confusing relationship of detention and punishment has a long history which has yet to be written. I can only gesture here some broad outlines. The medievalist Jean Dunbabin provides a useful typology distinguishing three kinds of detention: punitive detention, coercive detention, and custodial detention. Based on that, we can say that punitive detention (detention for purposes of punishment) was relatively rare before the 19th century. In the medieval and early modern periods, punishment took other forms like hanging, branding, transportation or monetary fines. Jails were used for custodial detention, to hold people in advance of trial, or while they awaited punishment, but were not in themselves considered a legitimate form of punishment. Prisoners of war and persons rounded up as political suspects during national security crises were also held in jail, but again, the point was to detain in custody rather than to punish. At the very worst, jailing could be considered a form of coercive detention, designed to be unpleasant enough to force someone to do something they would not otherwise do. Imprisonment for debt was the most common example of coercive detention in the early modern period. [3]

All detention was unpleasant, even for the members of the jail population not involved in any criminal proceedings. Even when prison itself was not considered a punishment, keepers had a wide latitude to commit violence in the name of making sure they did not run away (since keeping them from running away was the whole point of putting them in prison). Then, as often the case now, prisons were privately run by keepers who racked up fees for room, bedding, fuel, food and drink.

Nonetheless, unpleasant as custodial and coercive detention were, the objects of such detention were not considered criminals. This in turn gave them a sense of entitlements. For one thing, it was accepted that debtors (though not necessarily persons awaiting trial) should be allowed to see or even live with wives and children. Many prisons, had longstanding systems of inmate self-government, which put debtors in charge of the collection and distribution of charity among themselves. Prisoners agitated for the right to import food and drink from outside (better and cheaper than what the keeper served). They deluged magistrates with petitions about plumbing problems, visiting hours, the quality of the beer sold at the prison tap, and the need for a light on the stairwell, or an extra grate where prisoners could stand and beg passersby for money. The existence of so many complaints of course testifies to the badness of conditions, but it also testifies to the fact that detained people expected better. The understanding that detention was one thing and punishment another also gave prisoners a language in which to make claims. When a group of petitioners from the Chelmsford County Gaol in Essex asked judges in 1767 to “enforce the laws in our favor…that your petitioners may rejoice, so far as the nature of confinement will admit,” they acknowledged the legitimacy of their confinement but also expressed a sense of entitlement to some limited “joy.”[4]

At the end of the 18th century, understandings of detention changed radically. As freedom of movement became understood as a human right, the deprivation of movement itself could be seen as a deprivation of rights and hence as punishment. Enlightened reformers like Cesare Beccaria rejected the use of death or mutilation to punish relatively small crimes. They found something that could be humane, reforming, and (unlike hanging) adjusted to take into account variations in seriousness. Longer prison terms for greater offences, shorter for lesser, allowed judges to fit the punishment more closely to the crime, and thus, it was argued, demonstrate the principle that criminals should be punished in proportion to the degree that their act damaged society. The deprivation of freedom of movement in itself came to be seen as the punishment, in and of itself. And so was born the penitentiary—no longer a place to simply hold people, but a way to reform and punish.

The birth of the penitentiary, however, did not put an end to the need to detain people for non-punitive reasons. We now detain people punitively and non-punitively: that is, we put debtors, prisoners of war and persons awaiting trial into jails, and we also put convicted criminals into jails. We don’t think about the differences. The reformers who gave us the penitentiary hoping that it would make punishment more humane may therefore have inadvertently helped to make detention more like punishment. The result of this should be, in a good world, that we stop detaining people who have not been convicted of crimes. I fear that in this bad world, the result has been the opposite: we think of those we have detained as if they are convicted criminals.

The blurring of the lines between detention and punishment has reached crisis proportions in America. For one thing, debt imprisonment is making a comeback. Even though imprisonment for debt per se has not been legal since 1833, unpaid bills can now lead to jail terms in several different ways. Private collection agencies routinely get courts to issue warrants requiring debtors to appear, and then, when the debtor fails to turn up, have them jailed for contempt of court. Not paying alimony or child support likewise counts as contempt of a court order. The most enraging stories of all concern people sent to prison for unpaid Legal Financial Obligations [LFOs], such as traffic fines, court costs, fees levied by private probation companies, fees levied on prisoners. In other words, people are now in prison for having been in prison.[5] Moreover, they are held in prisons where criminals were held, not (as had been the case earlier) in separate prisons separated from felons. Debt is now treated under the sign of criminality in a way that it had not been before. That point about the lack of distinction is made powerfully by Alec Karakantsis, the lawyer who successfully sued the city of Montgomery Alabama in 2014 to stop the jailing of indigent debtors. “In the 1970s and 1980s,” he says, “we started to imprison more people for lesser crimes. In the process, we were lowering our standards for what constituted an offense deserving of imprisonment, and, more broadly, we were losing our sense of how serious, how truly serious, it is to incarcerate. If we can imprison for possession of marijuana, why can’t we imprison for not paying back a loan?” [6]

The lines between convicted criminals and persons detained on suspicion of having committed a crime are blurring as well. Wait times for trial have become so long that people serve the equivalent of sentences without having been found guilty of a crime, in county jails that are as bad as or worse than state and federal penitentiaries. In 2015 the public was shocked by the suicide of Khalief Browder, a teenager who had been locked up for three years on Riker’s Island, most of it in solitary confinement, for having been accused of stealing a backpack in a case that was never actually prosecuted.

Immigration is a third area in which lines between detention and punishment, while once theoretically clear, are now blurring in both theory and practice. Legal scholars have coined the term “crimmigration” to capture the ways in which immigration offenses, which are not criminal matters but rather matters of civil law, have increasingly been treated as crimes.[7] Detention centers for migrants facing deportation are increasingly indistinguishable from jails that house criminals; sometimes criminals and immigrants are literally held in the same place.[8] The Trump government has tried to get law enforcement authorities whose job it is to combat crime to divert their resources to hunting down undocumented immigrants instead. The latest zero-tolerance policy brings the full apparatus of the criminal justice system to bear on border-crossers, prosecuting them for crimes. This has not been changed by the latest order rescinding the previous order to separate families).

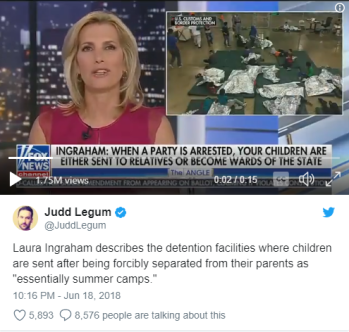

The Trump administration seems to be working the other side of ambiguity too, though. That is, it is trivializing or downplaying the de facto punitive aspects of detention, denying that its treatment of the detained amounts to punishment (or possibly torture). Recently Fox news host Laura Ingraham described the detention centers for children as “essentially summer camp.” Trump’s pardoning of former Maricopa Sheriff and current Senate candidate Joe Arpaio further signals the Administration’s trivializing of the injury that is done by detention. Arpaio’s many acts of cruelty and racism, and the sadistic conditions under which he held people in his desert tent-city concentration camps, are notorious. Significantly, the crime for which he was pardoned in advance of being tried was his unauthorized nine-hour detention of a Mexican man holding a valid tourist visa.[9] Trump’s routine invocation of his pet peeve, “catch and release,” further signals his refusal to see detention itself as an injury to the detained. In fact, what ‘catch and release” refers to is the sentencing of persons who were detained awaiting trial for illegal immigration to “time served,” i.e. a recognition by a court that they had already spent more time locked up than their offense would warrant. Trump makes these people who have spent weeks in detention sound like fish swimming happily away.

The ongoing horror of child separation at the border is enabled by the ambiguous status of detention as both not-punishment and punishment. The logic of separating children from parents who are in jail is that children cannot be put in jail because they have not been charged with a crime: detention here is interpreted as not-punishment. But of course, the separation is itself a punishment of the child as well as the parent, and it is precisely the trauma that is inflicted on the child that is valued by the Trump administration as a deterrent. It is worth noting that since the early modern period, letting families stay together (as in the case of debtors) was what distinguished “mere detention” from punishment: debtors fought for the right to live with or be visited by their families, and prison reformers who advocated sex segregation for felons thought that it was wrong in the case of non-criminal debtors to separate man and wife. Separation of families has conversely been a marker of criminalization. The crazy irony of the current situation, then, is that the theoretical non-punitiveness of detention imposed on children licenses the separation of children and parents for the purpose of punishing both parents and children.

All of this suggests that we need to think as clearly about detention as we do about punishment, to make it legible and visible as a category distinct from punishment, to define its terms, to define and defend the rights to which those who are in custody are entitled. The confusing nature of detention, the haziness of the line that separates it from punishment, I am suggesting, is an important part of the story of how the detained have come to be abused and of how that abuse is being justified. How that line got to be so hazy, and to what uses the haziness has been put, is a story that needs to be told.

Warm thanks to Joe Margulies and Maria Cristina Garcia for commenting on an earlier draft

[1] John Farmer to Nottingham, 8 November 1689 , HMC Finch II.259-60

[2] John Burnett, “The Last ‘Zero Tolerance’ Border Policy Didn’t Work,” NPR broadcast 6/19/2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/06/19/621578860/how-prior-zero-tolerance-policies-at-the-border-worked

[3] See Jean Dunbabin, Captivity and Imprisonment in Medieval Europe, 1000-1300 (Palgrave, 2002)

[4] Essex Record Office, Quarter Sessions Bundle (Epiphany, 1767), Q/SBb 248/2

[5] Brad Reid in Huffpost: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/brad-reid/may-you-be-imprisoned-for_b_8146874.html ACLU report https://www.aclu.org/files/assets/InForAPenny_web.pdf#page=6 ; Hannah Rappleye and Lisa Riordan Seville in the Nation https://www.thenation.com/article/town-turned-poverty-prison-sentence/

[6] “Debtors Prisons Then and Now,” https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/02/24/debtors-prisons-then-and-now-faq#.iQZqL8aDf

[7] César Cuauhtemoc García Hernández, “Creating Crimmigration,” Brigham Young University Law Review 2013, pp. 1457-1515.

[8] The Buffalo Detention Facility in Batavia, NY is a case in point. I owe this information to Maria Cristina Garcia.

[9] For the pardon, see Tom Jackman, “How ex-sheriff Joe Arpaio wound up facing jail time before Trump pardoned him,” Washington Post (August 25, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/true-crime/wp/2017/08/25/how-ex-sheriff-joe-arpaio-wound-up-facing-jail-time-before-trump-pardoned-him/?utm_term=.22e131571af4; “ACLU sues Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office for Illegal Arrest and Detention of US Citizen and Legal Resident” (August 19, 2009), https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-sues-maricopa-county-sheriffs-office-illegal-arrest-and-detention-us-citizen-and-legal; For more on Arpaio: William Finnegan, “Sheriff Joe,” The New Yorker (July 20, 2009) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/07/20/sheriff-joe; Joe Hagan, “The Long, Lawless Ride of Sheriff Joe Arpaio,” Rolling Stone (August 2, 2012) https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/the-long-lawless-ride-of-sheriff-joe-arpaio-20120802; Kelly Weill, “Inmates Left to Rot in 120-Degree Heat” The Daily Beast (June 21, 2017), https://www.thedailybeast.com/inmates-left-to-rot-in-120-degree-heat.

So interesting! And people are going to jail for medical debt too, as ProPublica reports: https://features.propublica.org/medical-debt/when-medical-debt-collectors-decide-who-gets-arrested-coffeyville-kansas/

LikeLike